We are half-way through August, and it feels wonderful to be writing on RUOT again. After a tumultous month and a half, I’m happily writing at my newly-put-together writing desk!

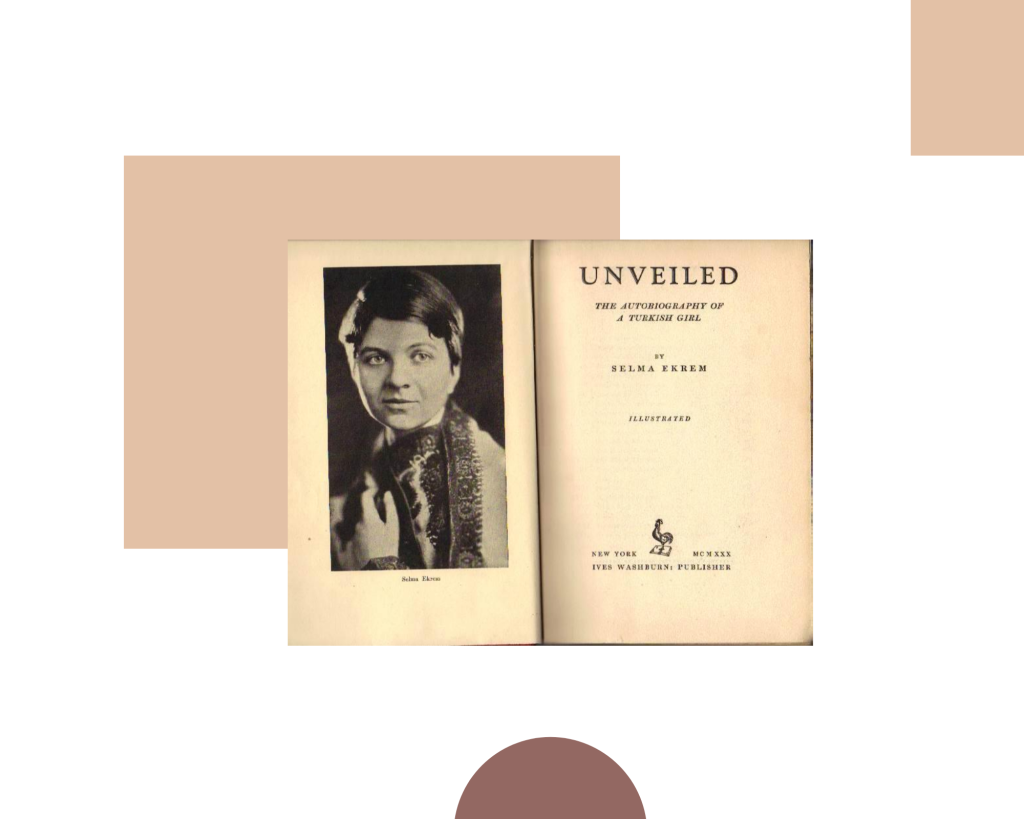

Since I moved back to Turkey, I’ve been meaning to re-read Turkish American writer Selma Ekrem’s Unveiled: The Autobiography of a Turkish Girl (1930).

And I was able to last weekend.

Ironically, the first time I read the memoir was when I was doing my master’s at Michigan. My questions regarding the lack of Turkish American writers led me to Selma Ekrem, the great Turkish writer and political activist Namik Kemal‘s granddaughter who immigrated to the U.S.

(Really, what is it about the lack of Turkish American writers?)

Selma Ekrem’s Unveiled: The Autobiography of a Turkish Girl recounts the trials and tribulations of displacement and cultural transmigration. As Ekrem negotiates her position as an immigrant woman in America, she meditates on the implications of the fall of the Ottoman Empire for Turkish women.

Born in Istanbul, Turkey in 1902, Ekrem moved to the United States after graduating from American College in Istanbul and later obtained U.S. citizenship.

Unveiled shows that Ekrem lives in a variety of states within the borders of the Ottoman Empire.

As a repercussion of Ekrem’s grandfather’s views against AbdulHamid II (reigned 1876-1909), Ekrem’s father, Ekrem Bey, is exiled in disguise. The Ekrems move first to Jerusalem after Ekrem Bey manages to secure his position as the new governor during the 1908 Young Turk Revolution. After the ethno-religious conflicts escalate in Jerusalem, the family crosses the border to Beirut where they are not welcome (since the Arab population in Lebanon

sought sovereignty from the Ottoman Empire). Then Ekrem Bey is assigned as the new governor to Rhode, Greece (which was also an Ottoman territory at the time). Within this state of perpetual transition, Ekrem’s move across borders leads to her transnational and transitional character.

Throughout her memoir, Ekrem shows the reader that rejecting the idea of veiling as a symbol of oppression is one of the various ways in which she transgresses gender norms.

Her critique of the veil and Islam is a bit tricky.

One might assume that she perpetuates the clichés about Muslim women. However, when we read between the lines, we can see that she is well ahead of her time, recognizing how religion is used as a tool to polarize and oppress. Even though she respects Islam and the Koran, the omnipresent strength of Allah stirs fears in her:

“Allah was a power even more supreme than my parents I had been told. A power that saw all and heard all. Even if one hid oneself under the bedcovers Allah would see one. I had a vague idea of one big ear and one big eye that followed me everywhere from morning until night” (39).

Her fear is valid when we remember that the notion of Islam as restrictive and oppressive is engrained in the teachings she receives. In the same complex vein, Ekrem perceives the veil as a pernicious force that shackles its victims. She recounts the lessons she receives by a hodja, priest in Islam, in Istanbul and writes that “…each time I saw him, I was chilled with fear and dislike” (177). After the lesson, she encounters a ceremony where her sister’s first veiling is celebrated. She writes about how the veil, inimical to her sister’s freedom, symbolically casts a darkness over her:

“A stranger to me now, a slim black bundle whose dark veilings cast over me a shadow, a shadow that seemed to grow mammoth and extend its clutches over my life. I felt cold with fear and anger. I did not want to see Abla in this black prison of a tcharhsaf” (178).

During the ceremony, Ekrem cries out in fear and resists her devout “Little Aunt” who tells her that she herself “will make [Ekrem’s] first tcharshaf” (178). She writes:

“For the first time, I found myself fighting alone a battle of dread and grief […] I felt my rising horror of veils

that covered faces and long skirts that entangled legs” (179).

And so she leaves:

“I wanted freedom now. This load of oppression was stifling me. The country was bound, the Turkish women were shackled…I heard tales from my American teachers: all that American women had done during the war…In that country I would find a solution for my life that had been one long struggle against tyranny…The very air of Istanbul crushed and strangled me…I had enough of running away like a criminal and silencing all the thoughts that sprang into me. Freedom I wished to have at all cost.”

Does she find freedom in the U.S.? Perhaps a semblance of it, since she decides to stay in the country. However, she finds herself compelled to face the challenges of displacement: discrimination, unemployment, culture shock, invisibility, and so forth.

Ekrem, with her fair complexion and green eyes, remains invisible to the American gaze because she does not match Americans’ racialized image of a Turk, “a huge person with fierce black eyes and bushy eyebrows” (302). Her initial encounter with invisibility occurs when she arrives in New York, and the customs officer mistakes her for an American. Ekrem states that she is Turkish, which fascinates the people around her:

“I saw vague ideas of daggers, veils, ephemeral silks and heavy incense drifting on their faces” (293).

Her identity is continually rejected by Americans whose vision is obscured by the binaries and

Orientalist fantasy:

“I realized why no one believed me…In America lived a legend made of blood and thunder. The terrible Turk…carrying daggers covered with blood, ruled the minds of the Americans” (302).

As she resists the exoticized views of her Turkishness in America, she realizes that she has been cast as “the Other” in Turkey, and she is cast as “the Other” in America, too:

“I who had dreaded to be recognized as a Turk in Turkey found it hard now to pass as a Turk in America” (301).

The liminal space she’s compelled to occupy in both countries, however, empowers her. She embraces the new space she creates in between two lands, two cultures.

It is then no surprise that Unveiled received positive reviews from prominent magazines such as the Times Literary Supplement, the Saturday Review of Literature and Chicago Daily Tribute when it came out.

Since then, however, Ekrem’s self-representation has been problematized by scholars such as Gonul Pultar, a scholar of cultural studies, who suggests that Ekrem assumes a Western/American voice that presents a westernized cooptation of her experience as a Muslim and Turkish woman. Ekrem’s choice to write in the language of the colonizer, English, is thus viewed as an integral part of the practice of, what Pultar calls, “self-orientalization.” By “selforientalization,” Pultar explains, “I designate the internalization, in native self images, of cultural representations of what has come to be summarized as Orientalism.”

The reading of the text from the perspective of self-orientalization is valid to an extent, as the title of the text reveals. (“Unveiled,” sort of titillating and colonial). Ekrem does utilize some of the Orientalist tropes that exoticize and at once stigmatize Muslim women as she resists the imposition of the niqab, the black veil that covers hair and body and face, on women. However, I argue that the internalization of Western modernity does not serve as the only formative part of self-representation in the text. Ekrem’s use of the stereotypical colonial perceptions operates as a strategy that problematizes and critiques the orientalist propensity to essentialize and categorize.

This is an argument that I delved into in a conference paper at MELUS in Las Vegas a few years ago, but all these academic arguments aside, I will say that Unveiled is a must-read for anyone who is interested in Turkish history, women’s rights in Turkey and in Turkish American experience.

Ekrem’s is a story of displacement and self-realization—a story of reconciliation between Eastern and Western cultural codes within a transcultural space as she grows into independence as a woman and an immigrant.

Have you heard of Selma Ekrem before, or any other Turkish American writers? I’d love to hear from you.

-Neri

what an interesting history, i love the perspective

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Beth. It’s a fascinating story, indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very nice and learned post. To date I’ve only read Forty Rules and some of the other books by Elif Shafak like: The Bastard of Istanbul. To the Q, nope — the name Selma Ekrem (and her work) was new to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person