It is October 14, and nearly a year since my last post here. Time flies, yes — it also stretches and shrinks when you’ve had the busiest, the most eventful year. It turns out that when big dates loom in the background, time seems to lose its meaning.

This past summer, I found myself traveling back and forth to the UK, teaching a summer course, finishing my book edits, running a new research project, and planning my wedding. Of course, it was all exciting and I loved all of it, but for little old introvert me, who often needs breathing space, there were moments when I wanted to pack up and move to a remote village in South America with five souls, plenty of fresh air, and cats. Well, instead, I learned that I was wildly lucky to find my soulmate when I least expected it – the kind that makes “when you know, you know” stop sounding trite. My husband shattered all my prejudices, swept away my past disappointments, and truly swept me off my feet. I learned it takes having the right person beside you to tackle all the complexities of a Turkish wedding — material for pages, and maybe a first novel. And I learned, too, what writing a book demands: dawn alarms, midnight shutdowns, the same loop on every day I wasn’t on campus teaching. It isn’t news that writing is no easy task, but when I was finishing the edits for my book, there were days when I’d roll out of bed at 6 a.m., sit down, write until midnight, sleep, repeat. Days that would have surprised my PhD-student self. Again, I learned throughout this process that the right person lightens the load and inspires you, instead of dragging you down.

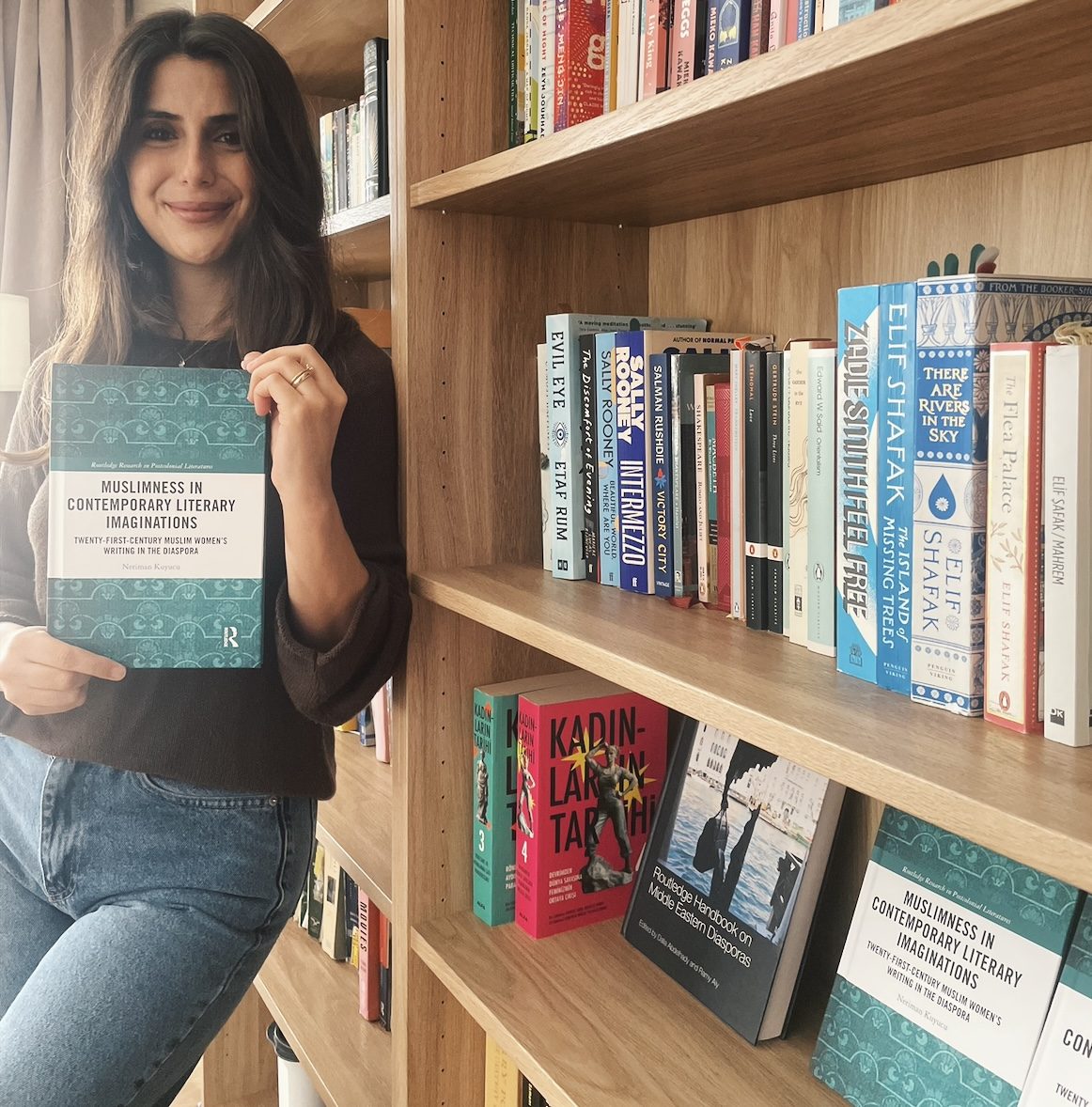

And today, October 14, my book is officially out. With the dust settled, I look back and see it all has fallen into place. (Feeling the weight of the book in my hands certainly helps.)

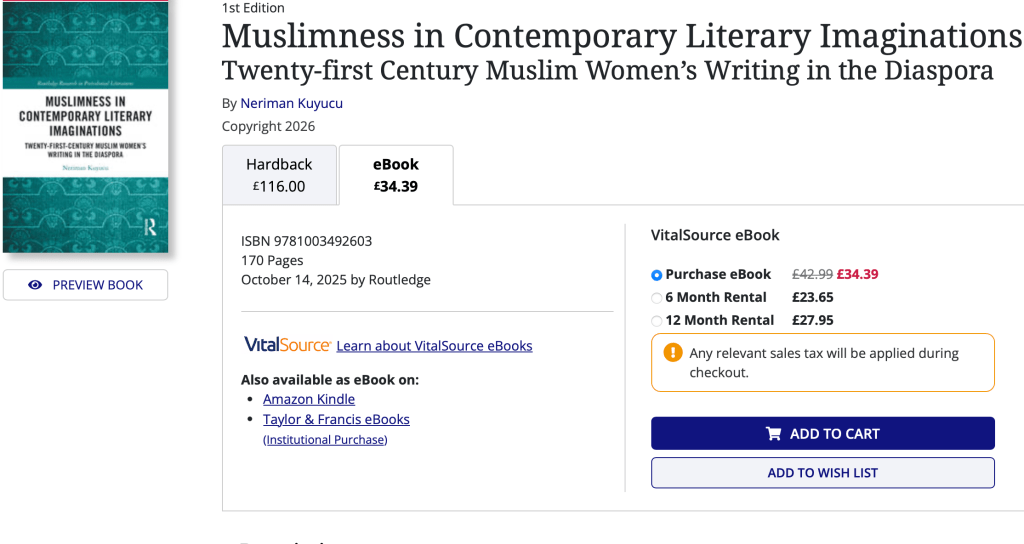

In 2018, I began to work on my dissertation at the University of Missouri, which would become Muslimness in Contemporary Literary Imaginations: Twenty-First-Century Muslim Women’s Writing in the Diaspora. Seeing it in print now as a revised, finished book, in the Routledge Research in Postcolonial Literatures series, paradoxically leaves me without words.

Still, I sometimes ask, against an ocean of books out there, what difference can one more make? But the question fades when I think of all the days, nights and years I have spent reading and writing, loving every minute. The question fades when I think of how, for thirteen-year-old me, who stumbled in English, doubted herself, yet fell deeply in love with the written word and its makers, this book is more than a scholarly work. For thirty-six-year-old me, now a doctor of words and literature, with the privilege of teaching, reading and writing (and still questioning myself and the world at times), it is more than an academic pursuit.

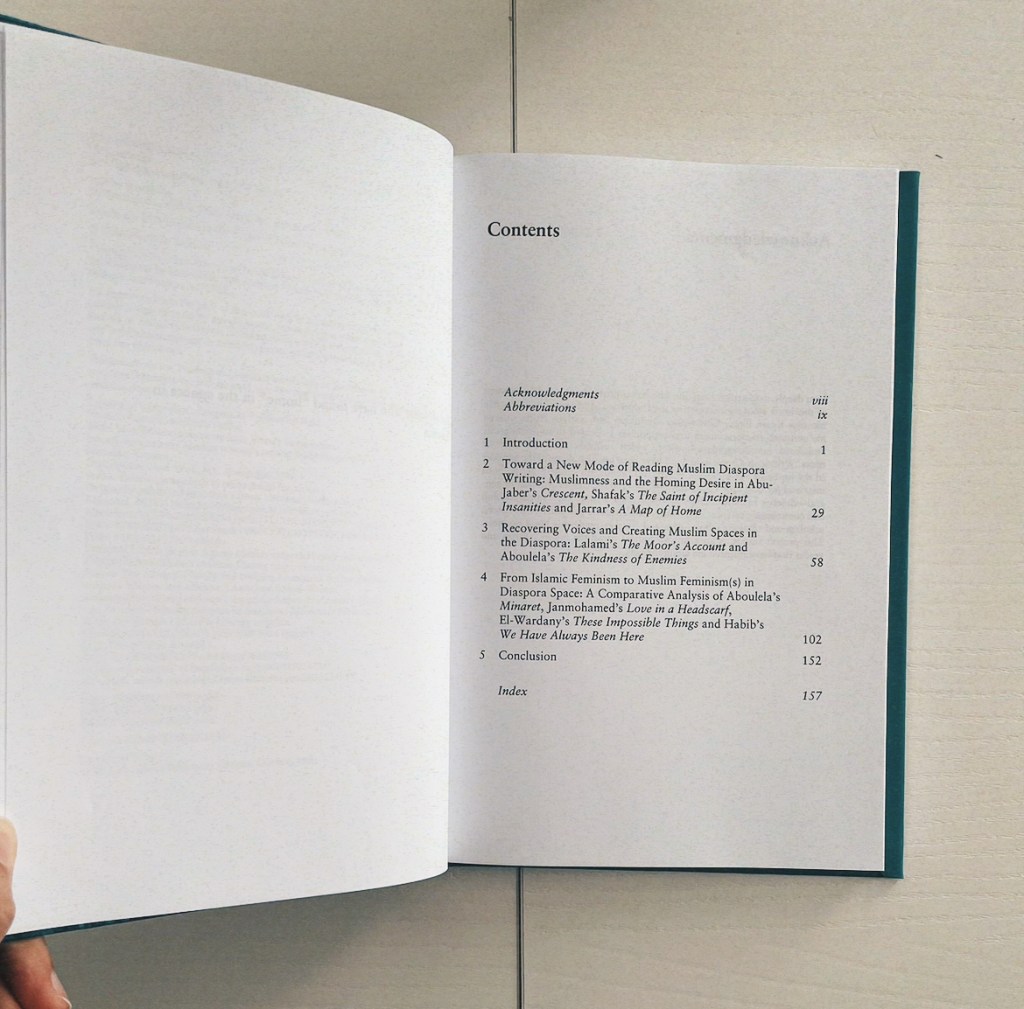

Muslimness in Contemporary Literary Imaginations is an honest work that challenges who gets to define “Muslimness” today. Drawing on Shahab Ahmed’s revolutionary theory of Islam ([2015] 2016) and various theories of diaspora, as well as literary and cultural studies, I move the conversation from orthodox Islamist and Western liberal or conservative narratives to the ways in which Muslim women writers define “Muslimness” themselves. As an interdisciplinary work, the book brings together literary, diaspora and Islamic studies. It is also a thank-you to scholars such as the late Shahab Ahmed, Avtar Brah, Scott Kugle, Haideh Moghissi and Edward Said, whose courage and intellect have changed the face of literary and cultural studies; a thank-you to the creative writers whose imaginations not only reshape the discourse but also make the world a better place (the best part was putting theory to work on pages penned by some of my favorite writers including, Elif Shafak, Randa Jarrar, Laila Lalami, Leila Aboulela, Samra Habib and Salma El-Wardany).

And, more importantly, it is a call for solidarity among women in the West (and beyond) who identify as Muslim, grounded in the conviction that no one has a monopoly on what it means to be Muslim in the twenty-first century.

I’ll end this post with the book’s conclusion:

“Throughout this project, I have underlined the significance of approaching Muslim diasporic writing through a postcolonial cultural studies method that unsettles the fixed categories of “Muslim” and “diaspora.” I have sought to demonstrate that both the Western ideological framework and orthodox Islamic tradition endorse a narrative that reduces Muslim identity to a monolith. The resurgence of Islamophobic rhetoric across the U.S. and Europe has reinforced this reductionism, calling for critical engagement with alternative perspectives. This book has pointed to the lack of emphasis on literary texts and the role of imagination in discussions on the Muslim diaspora. To address this gap in literary and diaspora studies, it has highlighted the need to reimagine the processes of departure, arrival, belonging and estrangement as situated at a Brahian point of dynamic encounter, in which the notion of Muslimness—what being Muslim means to an individual who identifies as one—is defined by lived experiences and personal reflections. Momin Rahman (2014) concludes his seminal work Homosexualities, Muslim Cultures and Modernity in a chapter entitled “Beginnings.” “A project such as this has no conclusion,” he writes, “given that it can only be a beginning to navigating the opposition of Muslim cultures and homosexuality” (137). I share similar sentiments about my project; I feel that writing this book is only the beginning of a crucial conversation.

It does not take long to recognize that oppositions, binaries and divisions dictate the discourse on Muslim identity within and outside the framework of orthodox Islam. Social media, the news, state policies and civil wars in the Muslim world, along with global reactions to these cycles, are driven by bias, stereotypes and competing claims of authentic Muslimness. Writing this book has reaffirmed how challenging it can be to evade labels if one identifies as a Muslim: “political, radical, nominal, cultural, spiritual, lapsed, modern, secular, conservative, queer”—the list is indeed long. This book’s primary goal was to intervene here, where the tension between Muslim identity, the ultimate Other in the post-9/11 context, and its representations reside. As a woman who grew up in a Muslim-majority country, lived in the U.S. and recently returned to her country of birth, it did not come as a surprise to me, of course, that political Islamist groups, secular organizations, governments, political parties, news outlets, imams and mullahs, academics, commentators, family members, friends and random individuals who speak about Islam and Muslims claim their right to do so. I have realized, over the years, that whether claims about “true” Muslimness are made by Muslims themselves or not is ultimately insignificant.

Perhaps, in more ways than one, some Muslims’ insistence on a single, authoritative vision of Islam does more harm, working to marginalize the voices of a vast number of Muslims, whose realities and beliefs vary. As Haideh Moghissi, Saeed Rahnema and Mark J. Goodman (2009) assert, there are around seventy-two sects within Islam itself, each group perceiving itself as the “saved sect” while deeming others as “misguided” (8). The heterogeneity of Muslim communities undoubtedly reflects the complex history of the Middle East and Islam, which is rarely addressed in discussions on Muslimness. Given the diversity of Muslim populations, how can a Lebanese in Michigan, a Nuremberg Turk, a Pakistani Londoner, or an Algerian in Paris possibly share a singular identity? It is highly problematic to state that they do. However, prevalent social categories of Muslims in the West reify the essentializing process where cultural, philosophical and spiritual discrepancies fall between the cracks.

Thus, the point of departure for this book was the Islamophobic rhetoric that has intensified following global events such as the “war on terror,” policies like the “Muslim ban” in the U.S. and the rise of far-right politics across Europe. Despite the drastic increase in anti-Muslim hostilities in the West, as I have demonstrated, the sociopolitical discourse has yet to shift to constructive discussions that highlight the diverse voices of Muslims. Conversely, Muslim identities continue to be homogenized as fundamentally orthodox and threatening. This biased framing is largely due to the history of Islamic studies in Western educational institutions dominated by Orientalist discourses. Islam has often been read through an orthodox lens, “through Sunni-Ash`ari thinkers, who denied human reason any ability to understand the rightness or wrongness of an act independent of God’s revelation” (Souaiaia 2021, 53). In this light, most Muslims find themselves navigating between an orthodox Islam that labels them “inauthentic” and a mainstream discourse that conflates Muslimness with Islamic strictures. In both cases, the notion of Islam as innately diverse, multifaceted and contradictory is actively resisted. Given this predicament Muslims face today, the questions that guided my project were: Who has the right to speak for and about Muslims in the contemporary sociopolitical landscape, where Muslims, despite their differences in many contexts, from national and ethnic to political and sexual, are persistently categorized as homogenous? Whose interpretations and perspectives on Muslims and Islam merit recognition, critical engagement and serious analysis? As I delved deeper into the research and analysis of the texts, the focus of my questions shifted to Muslims whose voices are sidelined within both the orthodox Islamic tradition and Western discourse. I have attempted to demonstrate throughout this book how such a small shift in focus within the discourse can lead us in the right direction toward a comprehensive, critical understanding of Muslimness. I was then led to identify a gap in the narrative— one in which Muslim writers and their works are often overlooked in discussions about Muslims— and eventually to this book. Here, I have explored the intersection of Islamic, cultural and literary studies and how this convergence informs contemporary perceptions of Muslim experiences, particularly in postcolonial and diasporic contexts.

Focusing on imagination and self-representation as a key sociocultural force in the context of the Muslim diaspora, I have sought to examine the diverse ways in which Muslim writers articulate complex and multifaceted conceptualizations of Muslimness at the critical conjuncture of culture, faith, gender, sexuality and diasporic experience. Ultimately, the goal was to underscore how contemporary fiction offers valuable insights into debates surrounding the diversity of Muslim subjectivities. To this end, my reconceptualization of “Muslim diaspora” as Muslim diaspora space has emerged as a mode of analysis, a guide that encourages pluralistic, complex readings of Muslim narratives. Muslim diaspora space is at the crux of this book, and I have offered a close analysis of the selected representative texts to illustrate how Muslim diaspora space as a lens:

- points to a supranational space of belonging that escapes the confines of ethnicity, nationality and religiosity through an emphasis on the processes by which Muslims reclaim their identity as Muslims and rightful citizens of their countries in the West;

- emphasizes the intersections of Muslimness and “homing desires” in the diaspora—the myriad ways in which Muslims redefine Islamic norms as it relates to their desires to feel at home;

- shifts the focus to the intersecting subjectivities that exist within discursive gaps, contesting the binaries of radical vs. infidel, or secular vs. pious;

- allows for a reading of Muslim narratives that transcends the writer’s level of piety, foreshadowing the collapse of the dichotomies that shape the discourse on Muslims;

- highlights the productive commonalities shared by Muslim literary texts, despite stylistic differences, including but not limited to their depiction of multi-dimensional Muslim characters and a conscious rejection of the Orientalist tropes that have historically defined the Muslim figure;

- last but not least, opens up intellectual and critical areas of inquiry by bringing to light how writers of Muslim origin diversify and queer Muslim writing.

The important point here is this: Muslim diaspora space as a mode of critical engagement can generate nuanced readings of diasporic Muslim experience. Rather than focusing on overly simplistic questions such as “Is the novel Islamic or secular? Western or Muslim?”—questions that fundamentally reinforce the dichotomies— I believe it is necessary to think beyond narratives of singular subjectivities. This discursive shift has, in turn, the potential to counter the current wave of anti-Muslim rhetoric that has a profound impact on the lived experiences of Muslims in the West. Although this project situates itself within the unsettling realities of the twenty-first century, this discriminatory rhetoric is not privileged in this project. Instead, I have aimed to shift the focus to presenting counter-narratives that emphasize solidarity, resistance and creativity to illuminate the various ways Muslim writers are reclaiming the narrative on Muslimness, undoing the invisibility that the hegemonic discourse perpetually inscribes on the name “Muslim.”

The selection of texts in this project is not intended to be exhaustive but is limited by time and scope. From Diana Abu-Jaber’s Crescent (2003) to Salma El-Wardany’s These Impossible Things ([2022] 2023), the books offer a representative framework for examining the primary themes of identity, culture, faith, sexuality and gender. Reading these diverse texts contrapuntally has revealed the complex spectrum of how Muslim women writers have been “writing back” since the early 2000s, underscoring the evolution of the Muslim narrative tradition. Beginning this book with the works of Diana Abu-Jaber, Elif Shafak and Randa Jarrar enabled me to revisit these crucial novels, which were published only a few years after the 9/11 attacks. This re-engagement highlighted their continuing relevance, particularly in their representations of what it means to be Muslim in the West, as well as the interconnections between them and the texts that were published later. Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account (2014) and Leila Aboulela’s The Kindness of Enemies (2015) illustrated how Muslim women writers re-present historically marginalized figures and experiment with historical fiction—a genre that is conventionally shaped by Eurocentric frameworks. Finally, reading the literary works of Leila Aboulela, Shelina Zahra Janmohamed, Salma El-Wardany and Samra Habib through the lens of Muslim diaspora space has brought to light how the boundaries of feminist engagement with Muslimness can be expanded, revealing a Muslim feminist discourse that reflects the shifting concerns, struggles and aspirations of Muslim women across diverse contexts and identities. Overall, this project has attempted to illustrate that Muslim writers engage in overlapping reconfigurations of Muslimness within contemporary literary imaginations. This literary reimagining of Muslim identity not only resists stereotypical representations; it also mediates and responds to the realities of the twenty-first century, including the rise of Islamophobia, anti-immigrant rhetoric, shifting concepts of citizenship and the destabilization of fixed notions of home.

One of the primary goals of this book was to establish literature as a crucial conduit for voicing Muslimness as a way of being and acting in the world. However, there are many potential avenues for future academic study of Muslim cultural production through the lens of Muslim diaspora space. For one thing, the scope of this study can be extended to various literary and cultural forms of diasporic experience. A close look at the contemporary cultural production of Muslim writers and artists points to an increasing engagement in the deconstructive project of rewriting, remapping and redefining the dominant hegemonic discourse. From Zeyn Joukhadar and Fatima Ashgar to Fatima Farheen Mirza and Zahra Barri, many writers—male, female and queer—whom I have not had the opportunity to include in this project—offer a nuanced understanding of Muslim identity marked by distinct lived realities. Concomitantly, these contemporary artists of Muslim origin respond to the need to revise thematic and textual limitations that Muslim artists have long encountered as “native informants.” Their works, which vary in genre, form and content, have a common motivation to build a bridge of meaningfulness between what it means to be Muslim and a citizen in the West—revealing the formation of a diasporic space where Muslims are actively reclaiming the narrative on Muslimness. Muslim diaspora space, as I have suggested, can be used to better comprehend the literary and cultural practices that are generating a discourse that reimagines a diasporic Muslim subjectivity that is innately diverse, complex and synchronously Muslim. Returning to Rahman, I shall conclude this project by emphasizing the idea of a beginning. This chapter is not a conclusion but an invitation to continue the conversation— to challenge boundaries and carve out new trajectories in the field of Muslim literary studies. ”

References:

- Rahman, Momin. 2014. “Beginnings.” Homosexualities, Muslim Cultures and Modernity. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moghissi, Haideh, Saeed Rahnema, and Mark J. Goodman, eds. 2009. “Introduction.” Diaspora by Design: Muslims in Canada and Beyond. University of Toronto Press.

- Souaiaia, Ahmed E. 2021. Human Rights in Islamic Societies: Muslims and the Western Conception of Rights. Routledge.