“If you want others to be happy, practice compassion,” Dalai Lama XIV famously writes in The Art of Happiness (1998), “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.”

It is an intriguing concept, compassion. And an ambiguous one. Since it is considered to be the path leading to love, happiness, and greater awareness, over the centuries, world religions, as well as scientific studies have over the centuries investigated its meaning(s) and the ways in which we can practice it to achieve the goal of a fulfilling life.

‘ “My religion is kindness,” says the Dalai Lama; faith that moves mountains is worthless without charity, said St Paul; the Golden Rule was the essence of Torah, said Rabbi Hillel: everything else was “only commentary”. The bedrock message of the Qur’an is not a doctrine but a summons to build a just and decent society where there is a fair distribution of wealth and vulnerable people are treated with absolute respect.”

Karen Armstrong, author of The Great Transformation: The World in the Time of Buddha, Socrates, Confucius and Jeremiah (2011)

The practice of compassion is central to human survival, but what exactly does the practice of compassion entail? What is “compassion”? Is it a moral force, as spiritual leaders have postulated?

Does it mean “to pity” and “suffering together with another, participation in suffering; fellow-feeling, sympathy” as Oxford English Dictionary defines it.

Is it an emotional response? Can it be improved through practice?

More importantly, how can we cultivate compassion in the contemporary world marked by global disorder and chaos? What does it mean to practice compassion at this historical juncture when the media is oversaturated with images of violence and suffering?

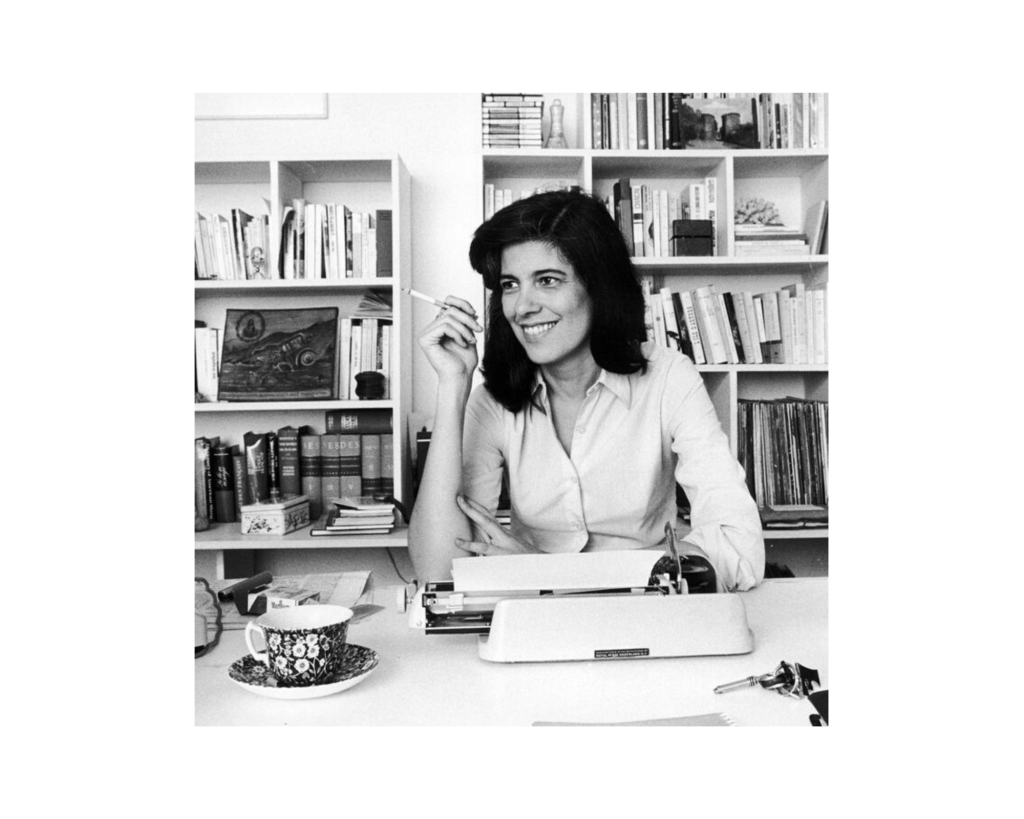

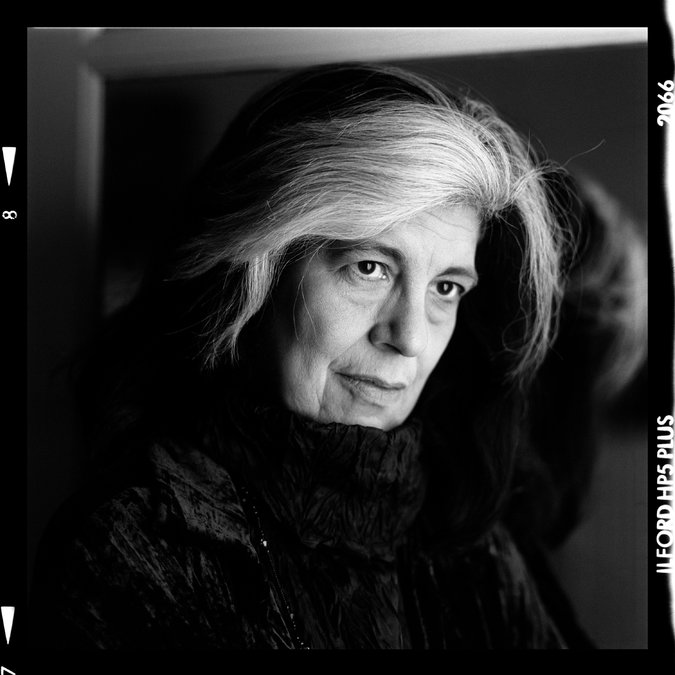

These are the questions that Susan Sontag (1933– 2004) explores in her brief book, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003).

Sontag reflects on visual representations of war and violence, raising a series of interlocking questions: What’s the purpose of war photography? How does it affect the “spectator”? How do we respond to the increasing flow of information about the atrocities of war? Do such horrific images and stories of war evoke compassion or make us indifferent?

She writes:

“Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers. The question is what to do with the feelings that have been aroused, the knowledge that has been communicated. If one feels that there is nothing “we” can do—but who is that “we”?—and nothing “they” can do either—and who are “they”?—then one starts to get bored, cynical, apathetic.

And it is not necessarily better to be moved. Sentimentality, notoriously, is entirely compatible with a taste for brutality and worse. (Recall the canonical example of the Auschwitz commandant returning home in the evening, embracing his wife and children, and sitting at the piano to play some Schubert before dinner.)

People don’t become inured to what they are shown—if that’s the right way to describe what happens—because of the quantity of images dumped on them. It is passivity that dulls feeling. The states described as apathy, moral or emotional anesthesia, are full of feelings; the feelings are rage and frustration. But if we consider what emotions would be desirable, it seems too simple to elect sympathy.

Remembering and showing compassion is crucial; however, is it enough to just remember and sympathize with those in pain? Sontag further delves deeper into the question of what it is that we actually remember when we see images of violence without understanding the proper context.

She suggests:

“Perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it – say, the surgeons at the military hospital where the photograph was taken – or those who could learn from it. The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be.”

Sontag acknowledges the pivotal role that visual representations play in drawing attention to suffering—particularly if they lead to awareness and action:

“The images say: This is what human beings are capable of doing—may volunteer to do, enthusiastically, self- righteously. Don’t forget. This is not quite the same as asking people to remember a particularly monstrous bout of evil. (“Never forget.”)

Perhaps too much value is assigned to memory, not enough to thinking.”

But she wants us to question our positions looking at an image of suffering; sympathizing with the pain in an image, she implies, is not sufficient:

“The imaginary proximity to the suffering inflicted on others that is granted by images suggests a link between the faraway sufferers—seen close-up on the television screen— and the privileged viewer that is simply untrue, that is yet one more mystification of our real relations to power.

So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence. To that extent, it can be (for all our good intentions) an impertinent—if not an inappropriate—response. To set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering, and may—in ways we might prefer not to imagine— be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others, is a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.”

In addition to thinking about the suffering portrayed in an image, Sontag wants us to question whether our privileges may be linked to the pain of others. She asks us to critically think about the social, political, and economic implications behind these emblems of suffering and our reactions to them.

As she writes:

“Such images [can be] an invitation to pay attention, to reflect, to learn, to examine the rationalizations for mass suffering offered by established powers. Who caused what the picture shows? Who is responsible? Is it excusable? Was it inevitable? Is there some state of affairs which we have accepted up to now that ought to be challenged? All this, with the understanding that moral indignation, like compassion, cannot dictate a course of action.”

What, then, is the best we can do to acknowledge the suffering of others? Do you think compassion is sufficient? Can it connect us with those caught in the middle of a revolution, a global crisis, or a civil war?

I’ve also been thinking about the coronavirus crisis which has affected the whole world, both the so-called developed and developing countries. The fact that our privileges have been amplified in this context only adds another layer to the complex question of what “compassion” means.

I don’t have an answer to these questions, but I do think that engaging with these questions could be a good start. After all, as Sontag emphasizes:

“There’s nothing wrong with standing back and thinking. To paraphrase several sages: “Nobody can think and hit someone at the same time.”

More on Susan Sontag:

You can read the first chapter from Regarding the Pain of Others on The New York Times here.

Interview with Sontag, “The Art of Fiction,” Paris Review

Interview with Sontag, The Rolling Stone

A thought provoking post on a concept that takes much reflection to begin to understand let alone master or judge it’s value.

I remember reading many books by the Dalai Lama in my 20’s and struggling with how to practice compassion towards someone I held a grievance towards, but his advice is also practical and so I followed the suggestions and found a way. Looking at it now I think it is a prerequisite step to self healing and ultimately that is part of what we can all do for the planet, heal something within and be a role model by our behaviour, for the highest good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Claire, I absolutely agree. Could you share some of the ways in which you’ve come to practice it–only if you don’t mind sharing, of course 🙂 -Neri

LikeLike

“The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be.” The whole post is thought-provoking, but this quote in particular sticks with me. It makes me think about racial violence in America – how many times I’ve seen viral videos of police brutality but not *done* anything other than feel bad. I think Sontag got it right: it is not enough to feel compassion if you don’t act on it or learn from it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not every image of violence affects me, but one in particular did. When I was about 12 I saw a color photograph of a dead prostitute laying face down on a street somewhere in Asia. It struck me that she was very much discarded, that somewhere along the line the normal protocol of putting a sheet on the dead, collecting the dead for burial, reporting the dead, somewhere that had not happened, rather she was left like trash, by a society who didn’t value her as anything more than a disposable consumer good. I saw at once a person, and also a person who had been treated not as a person. I had always held an imaginary divide between myself and women of the sex trade or exotic dancers, the taboo women, but the image dissolved that for me, it turned them into people. Once a group of musicians came to my school with all the horns and stringed instruments, to see which ones the students gravitated towards if any. I think that perhaps violent images are similar, that they are always moving to a particular person. There is a story about Siddhattha Gotama leaving the palace and seeing birth, sickness, aging and death, meeting those realities, I think violent images still serve the youth in a similar fashion, that many parents create an imaginary world where there is not injustice on a grand scale and uncertainty on a grander one, but images of violence can break that facade. I wish there was a better way to present the truth of violence publicly, while still offering a choice to the viewer, children and sensitive people have trouble not being showered with a deluge of constant violence. Perhaps it’s a necessary truth over done, but I would say it’s more important to end the underlying sources than to end the over presentation of the images. Still hoping for world peace in someday. 🕊️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully said… Thanks for sharing ❤

LikeLike

great post, and all the more relevant considering what we’re living through right now. Sontag’s comment on apathy and passivity made me think about how the internet has magnified how much others’ suffering we could possibly be exposed to. It’s harder in many ways to stop and really think about what youre looking at because of the sheer scale of suffering that the internet can lay bare. on the one hand I think its positive that we’re able to hear so many people’s stories, but on the other hand I wonder to what extent we’re able to really engage with those stories in a compassionate way, according to what Sontag outlines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Fatma, I absolutely agree. Although the images of suffering draw attention to what’s going on, we are getting desensitized to others’ suffering because the media is oversaturated with such images and stories. Having read this work, Sontag would probably say—as long as these images urge us to think about the various systems that cause such suffering and to challenge them, they are doing what they’re supposed to?

LikeLike

This is wonderful. She was truly an inspirational lady.

LikeLiked by 1 person