Disclaimer: I have stopped actively working on this list/project; I’ve found myself continuing reading migration novels, which is my area of expertise, and I have so many articles to write, and conferences on my schedule. But I am keeping the reading list on here; these books, I will have to read sometime. And I will certainly update this page if I read and write about any of these books presented on the list. Happy reading!

Reading around the world challenges abound on the internet, and I admire and adore anyone and everyone who makes the decision to participate in a global reading challenge, no matter what their motivation is. As David Damrosch highlights:

Literature is not a simple mirror reflecting; rather, it refracts the culture from which it comes. But it provides a way to think deeply—it’s a little bit like the slow food movement in a world of fast foods. To read deeply and attentively a rich work of literature gives us a unique way of thinking about ourselves and our place in the world.

While reading (around) the world “challenges” are a wonderful tool through which we can read outside our comfort zone, the issue with some of these lists is that they, often unintentionally, perpetuate the nationalization of literatures, as well as the fetishization of stereotypes (and sometimes trauma, e.g. genocides, repression, suffering). In addition, male writers are consistently over-represented on these lists–mainly because nationally and internationally-acclaimed texts have usually been, for sociocultural and political reasons, penned by male writers. Then, there’s the problem of disproportionate representations of writers who are part of the global elite and write in English. It is quite difficult to find translations from each country, which brings the issue of global capitalism and its inequalities to the fore within the context of world/global literatures. I will not get into the scholarly debate on the terms “world”, “global”, and “international” literatures, but the links I have provided at the end of this post will offer some insight into the ways in which World Literature is being reconceptualized. What I’d like to underline, however, is how reading around the world lists, like most syllabi reading lists, often reflect hyper-elitism and gender-based disparity that permeate the global publishing market.

As emphasized in the article, “What is Global Literature?” (2013) published on n+1:

Global Literature can’t help but reflect global capitalism, in its triumph, inequalities, and deformations. In the English language, World Literature has its signature writers: Rushdie and Coetzee at the lead, and Kiran Desai, Mohsin Hamid, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie among the younger charges. It has its own economy, consisting of international publishing networks, scouts, and book fairs. It has its prizes: the Nobel, of course, but more powerful and snazzier is the Man Booker, and the Man Booker International. Its political arm is PEN. And it has a social calendar full of literary festivals, which bring global elites into contact with the glittering stars of World Lit. Every year, sections of the dominant class fly from Mexico City to have Julian Barnes sign books in Xalapa, or from Delhi to Jaipur to be seen partying with Mario Vargas Llosa. The Hay Festival, started in Hay-on-Wye in rural Wales, now has outposts in Dhaka, Beirut, Nairobi, and elsewhere. “Hay Festival in Cartagena de Indias” is an accidentally funny phrase — Sí, hay festival — redolent of a strange new intimacy between global north and south.

What about the role of the academy in this context?

It is argued that:

The key institution in the creation of World Literature has not been the literary festival, or even the commercial publishing house, but the university.

Every World Lit writer seems to have an appointment. Pamuk teaches at Columbia; Paul Muldoon at Princeton; Junot Díaz at MIT. University-produced postcolonial theory was also part of the education of World Lit. Rushdie had crucial friendships with Edward Said and Homi Bhabha, as did Ngugi with Gayatri Spivak. Increasingly writers from Calcutta and Cape Town attend MFA programs in East Anglia or Syracuse. Universities that celebrate their commitment to diversity — of cultural identity, if not class background — owe it to themselves to hire writers of odes to hybridity.

World Literature today is thus canonized by the academy, and it wouldn’t be wrong to say that it is run like a private club by the global elites. “Today’s World Lit is more like a Davos summit,” it is stated in the article, “where experts, national delegates, and celebrities discuss, calmly and collegially, between sips of bottled water, the terrific problems of a humanity whose predicament they appear to have escaped.” This is merely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to discussions on World Literature. I wanted to begin with this brief overview because I kept, what David Damrosch calls, World Lit’s uneven playing field in mind as I was compiling my list. It has been challenging -might I add- to take a more mindful approach that refrains from over-representating globally and traditionally acclaimed male writers. So, this is by no means a perfect reading list, and I’m conscious of the limitations of such a list.

Despite the challenges, however, I’m pleased with my reading around Asia list (which is and will be work in progress). The meticulously curated reading list down below is mainly (not entirely) comprised of contemporary literary works (published post-2005) by female and queer writers of Asian origin. I must add that I still need help finding queer and/or female Central Asian voices. Due to repression and censorship, publishing in the post-soviet countries such as Uzbekistan and Tajikistan is evidently an arduous process, but if you know of immigrant writers from Central Asia, or if you are one (self-publishing perhaps?), please let me know–I will keep updating my list as I’m introduced to more writers who are writing from “the periphery.”

So, how will I do this?

No strict rules, really.

My goal is to read one or two books from each Asian country–as defined by UNSD— by writers who are deeply connected to these countries and their heritage (even if some on the list are citizens of the Global North) and to write about them here and/or on my Instagram page. It would be ideal to finish reading all the listed books in a year, but with a full-time job, it may not be possible, and that is okay. I’d like to take my time, savor each text, and read them deeply, if you will.

By reading these books, I hope to start a conversation about the texts, the countries, the writers, yes, but I also aim to explore the various ways in which national borders are transgressed in these works. Some of the questions I will be considering are as follows: What makes a “national writer”? How is a national (literary) identity formed? How can we read/understand these texts from different countries as a whole? How do these works contribute to our understanding of world literatures?

Feel free to read with me, or pick a book from the list and read it in your own time– and please let me know if you have any suggestions and recommendations.

Happy reading!

P.S.: Thank you to everyone who recommended books to me as I was compiling my list–you’ve been a great help!

Reading Around Asia List

The World Bookshelf Challenge, 2021

1. Armenia:

- Bringing Ararat by Armand Inezian, 2010 ✓

- Three Apples Fell from the Sky by Narine Yuryevna Abgaryan, 2016, Trans. by Lisa C. Hayden, 2020

2. Azerbaijan:

- Uçan Giden Bir Kus (A Bird That Flies Away) by Feriba Vefi, originally pub. in 2002, translated into Turkish by Lale Javanshir in 2016

- The Incomplete Manuscript by Kamal Abdullayev, translated by Anne Thompson, 2013

3. Afghanistan:

- Sparks Like Stars by Nadia Hashimi, March 2021

- A Curse on Dostoevsky by Atiq Rahimi, originally pub. in 2011, translated by Polly McLean 2013

3. Bahrain:

- Unicorn: The Memoir of a Muslim Drag Queen by Amru- al Kadhi, 2019

- Bahrain: Political Development in a Modernizing Society by Emile Nakleh, 2011

4. Bangladesh:

- Shameless by Taslima Nasreen, 2020

5. Bhutan:

- Folktales of Bhutan by Kunzang Coden, 2016

- The Circle of Karma by Kunzang Choden, 2005

6. Brunei:

- Written in Black by K.H. Lim, 2015

7. Cambodia:

- In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner, 2012

8. China:

- The Chilly Bean Paste Clan by Yan Ge, originally pub. in 2013, translated by Nicki Harman, 2018

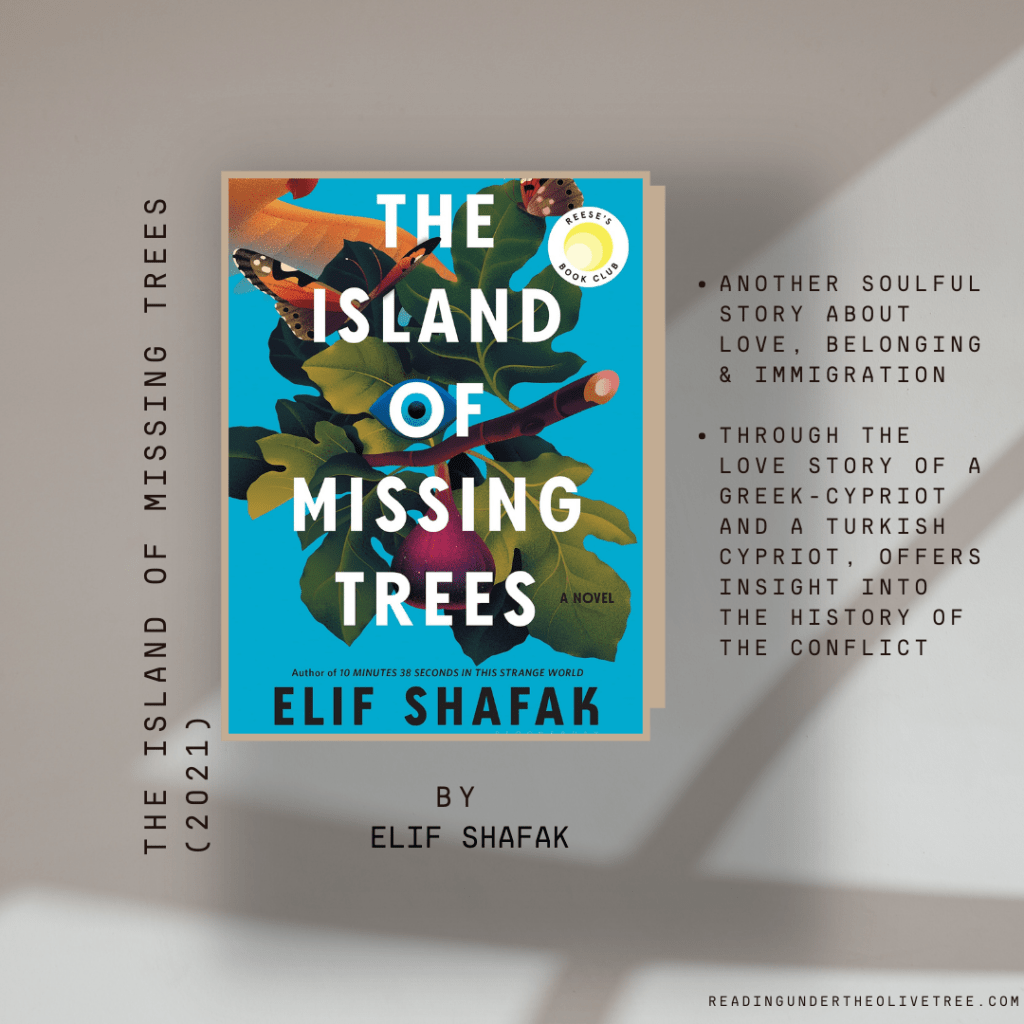

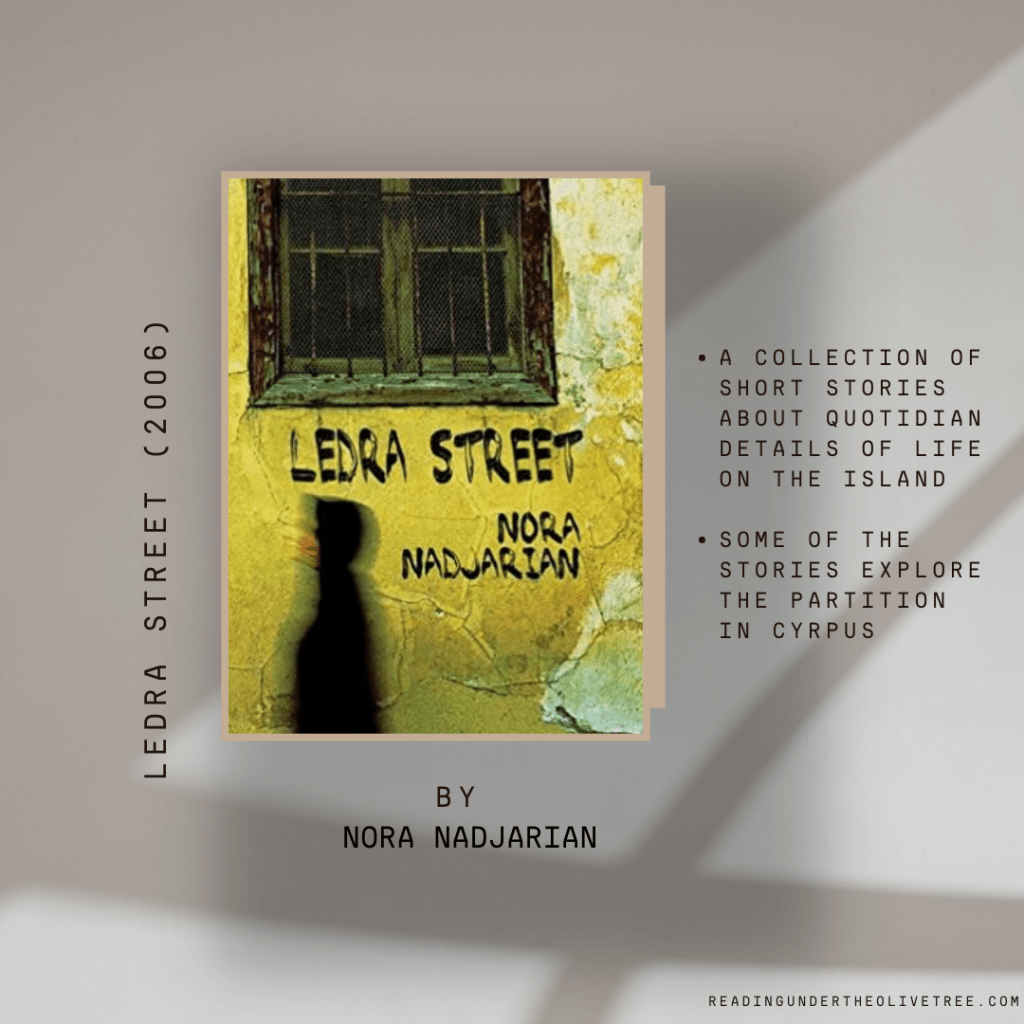

9. Cyprus:

What I read: This Way Back by Joanna Eleftheriou: A timely narrative about identity, faith, and belonging, This Way Back opens with Joanna Eleftheriou in Cyprus for her father’s funeral, a Greek Cypriot immigrant in New York whose dream of returning home to Cyprus became more and more intricate. Read more and see my interview with the writer here.

Other books from and about Cyprus you can add to your list:

10. Georgia:

- Madrabaz Kvaci (Kvachi in English) by Mikheil Javakhishvili, 1925, translated into Turkish by Parna-Beka Cilasvili, 2017

- The Literature Express by Lasha Bugadze originally pub. in 2009, translated by Maya Kiasashvili, 2014.

11. Indonesia:

- The Original Dream by Nukila Amal, originally pub. in 2003, translated by Linda Owens, 2017

12. Iran:

13. Iraq:

- Revolt Against the Sun by Nazik al-Malaʾika, originally pub. in 2020, translated by Emily Drumsta, Feb. 2021.

14. India:

- Whereabouts: A Novel by Jhumpa Lahiri, originally pub. in 2018, pub. in Eng, April 2021 ✓

- Well-Behaved Indian Women by Saumya Dave, 2020. ✓

- The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy, 2017.

15. Israel:

- The Liar by Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, 2019.

16. Japan:

- An I-Novel by Minae Mizumura, trans. 2021 ✓

- Where the Wild Ladies Are by Aoko Matsuda, originally pub. in 2016, translated by Polly Barton, 2020

- Before the Coffee Gets Cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi, 2015 ✓

- Snow in Amman: An Anthology of Short Stories from Jordan by I. Rida Mahmood (Translator), Alexander Haddad (Editor), 2015

17. Kazakhstan:

- The Dead Lake by Hamid Ismailov, translated by Andrew Bromfield, 2015

18. Kyrgyzstan:

- Jamilia by Chingiz Aitmatov, originally pub. in 1958, translated by James Riordan, 2007

19. S. Korea:

20. N. Korea:

- Friend: A Novel from North Korea by Paek Nam-Nyong, 2020

- Accusation by Bandi, 2014, Trans. by Deborah Smith, 2017

21. Kuwait:

- The Pact We Made, by Layla AlAmmar, 2019

- Silence is a Sense by Layla AlAmmar, March 2021

22. Laos:

- How to Pronounce Knife by Souvankham Thammavongsa, 2020

- The Song Poet: A Memoir of My Father by Kao Kalia Yang, 2016

23. Lebanon:

- Louder Than Hearts: Poems by Zeina Hashem Beck, 2017

24. Maldives:

- Dhon Hiyala and Ali Fulhu by Abdullah Sadiq, originally pub. in 1978, translated from Dhivehi to English by Fareesha Abdullah and Michael O’Shea, 2004.

25. Malaysia:

- We, The Survivors by Tash Aw, 2019

- The Rice Mother by Rani Makina, 2002, 2004.

26. Mongolia:

- Mongol by Uuganaa Ramsay, 2013

27. Myanmar:

- Miss Burma by Charmaine Craig, 2017

- Myanmar’s Enemy Within: Buddhist Violence and the Making of a Muslim ‘Other’ by Francis Wade, 2017

28. Oman:

- Earth Weeps, Saturn Laughs by Adbulaziz Al Farsi, translated by Nancy Roberts, 2013.

29. Qatar:

30. Palestine:

- Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa, 2020

- The Arsonists’ City by Hala Alyan, 2021 ✓

31. Pakistan:

- Threading My Prayer Rug: One Woman’s Journey from Pakistani Muslim to American Muslim by Sabina Rehman, 2016.

32. Philipines:

- The Mango Bride by Marvin Soliven Bianco, 2013

- The Last Time I Saw Mother by Arlene J. Chair, 1996

33. Russia:

- Compartment No. 6 by Rosa Liksom, originally published in 2011, Translated by Lola Rogers, 2016.

- Zuleikha by Guzel Yakhina, translated by Lisa C. Hayden, 2019.

34. Saudi Arabia:

- A Girl Like That by Tanaz Bhathena, 2018.

35. Singapore:

- The River’s Song by Suchen Christine Lim, 2014.

36. Sri Lanka:

- The Boat People by Sharon Bala, 2018

37. Syria:

- The Thirty Names of Night by Zeyn Joukhadar, 2020

- The Clothesline Swing by Danny Ramadan, 2017

- A Land of Permanent Goodbyes by Asia Abawi, 2018

38. Taiwan:

- An Excess Male by Maggie Shen King, 2017

39. Tajikistan:

- My Neighbourhood Sisters & The City Where Dreams Come True by Gulsifat Shakdi, 2016

40. Thailand:

- Arid Dreams by Duanwad Pimwana, originally pub. in 2014, translated by Mui Pooposakul, 2019

41. Timur-leste***: still looking for a book

- Women and the Politics of Gender in Post-Conflict Timor-Leste: Between Heaven and Earth, edited by Sarah Niner, 2016

42. Turkey:

- Women Who Blow on Knots by Ece Temelkuran, originally pub. in 2013, translated by Alexander Dawe, 2017

- The Highly Unreliable Account of the History of a Madhouse by Ayfer Tunc, 2009, translated by Feyza Howell, 2020

43. Turkmenistan:

- The Tale of Aypi by Ak Welsapar, 2016

44. United Arab Emirates:

- Temporary People by Deepak Unnikrishnan, 2017

45. Uzbekistan:

What I read:

In Quest of a Homeland: Recollections of an Emigrant (2005) tells the story of Yousuf Mamoor, an Uzbek immigrant forced to leave his hometown, Kokand in eastern Uzbekistan, in 1930 at the age of fourteen. Read my full reflection here.

Other books from Uzbekistan you can add to your list:

46. Vietnam:

- Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai, 2011

- When Heaven and Earth Changed Places: A Vietnamese Woman’s Journey from War to Peace by Le Ly Hayslip, originally pub. 1989, translated by Jay Wurst, 1993

- On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong, 2019

47. Yemen:

- A Land without Jasmine by Wajdi al-Ahdal,translated by Willian Maynard Hutchins 2012

More on World Literature:

Apter, Emily. The Translation Zone: A New Comparative Literature. Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2011.

Damrosch, David. What is world literature? Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press., 2003.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, Soret, Frédéric Jacob, Oxenford, John,Eckermann, Johann Peter. Conversations with Eckermann: being appreciations and criticisms on many subjects. Washington, M.W. Dunne. 1901.

Haen, Theo d’. The Routledge concise history of world literature. London : Routledge, 2012.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. Death of a discipline. New York : Columbia University Press, 2003.

n+1, “What is Global Literature?”

A World of Literature: David Damrosch’s literary global reach

Henitiuk, Valerie. The Single, Shared Text? Translation and World Literature. World Literature Today, (86)1, 30-34. 2012

Cyprus: This Way Back by Joanna Eleftheriou, 2020 i love your list and your challenge, but is Cyprus part of Asia?

I love your enthusiasm.. Now that you have finished your phd what work do you do? will you read all these books in English or turkish translation?

Your wrrting is so interesting – do you not feel the need to write a book yourself?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Basia, I love the question about Cyprus, and all the other questions, really. To answer the four questions:

1- Cyprus is actually between the Middle East and Europe, like Turkey and is considered part of Asia by UNSD. BUT when I asked the author of This Way Back about her book being part of my list (she’s a good friend of mine), she said “I actually open it by stating the distance of my village from Beirut for the express purpose of destabilizing the idea that we are European because we speak Greek. Plus, I always thought Ancient Cypriot art looked weird until I saw it in an exhibit with art from Central Asia and the “near East”!”

2- I moved back home to Istanbul after a decade in the U.S. and teach writing at a university here, and I’m loving it!

3-I will be reading the books in English–with two or three exceptions. Some books from Central Asia have not been translated into English yet so I’m planning to read their Turkish translations.

4- I appreciate it–I do want to write my own book some day. The problem is I have many ideas for a novel, and I cannot even decide which one I should go for. I may just do a writing workshop somewhere in the summer to get started once the pandemic is over.

Thanks for your comment 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for answering. I appreciate the comment. My stepfather spent some time in Cyprus as a refugee during the second world war and I am afraid in my ignorance I assumed it was more European than otherwise. But I can see the truth. I have only been to Turkey once though I have a cousin who is Polish who lives in Istambul. I went to Antalya about eight years ago, which was fascinating in many ways.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I loved your question because it actually raises another crucial question about the constructed nature of borders and nations. I love these countries/islands like Turkey and Cyprus that are located in a liminal space because they urge us to ask: what makes them European? And what makes them Asian? Do they need to have a single national/continental identity? Whose interest does it serve to categorize these countries as Asian or European? And so forth.

Antalya is lovely, but you should visit Istanbul 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Antalya was indeed lovely but it was very disconcerting to find that all historical aspects of Christianity had been totally eradicated. I had been to Syria two years previously, and Damascus seemed to have the Islam/Christianity configuration sorted. I was expecting more of the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. I’ve actually never been to Antalya, since I lived abroad for a while. I’m envious though that you got to visit Damascus!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Damascus was life changing for me. We went for a weekend, jsut before the troubles started. I have written about it on my blog. I don’t know how to post a link on here, but I can try and work it out if you like

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a fantastic challenge and a fascinating list, which I will be bookmarking for my own use in the future! I’ve read a few titles from your selection but most are new to me, so I look forward to reading your impressions as you go through them.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Eleanor, let me know if you have any recommendations for the list!

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is such a great challenge! I will definitely have to save your list for when I’m done with my own thesis and will hopefully have loads more spare time that I can use for reading 😅

And I really relate to you having shoved aside Turkish books while you were studying English literature, too. I’ve read so few German books in the past couple of years that I really want to make more of an effort and get back to them this year! And I was also hoping to read some Russian classics in 2021, since I’ve been studying the language for almost two years now and really want to delve more deeply into the culture and Russian history. But hopefully that can serve as a starting point for reading more internationally in the future!

LikeLiked by 2 people

That sounds like a good plan 🙂 Good luck writing your thesis! What is it about?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I’m actually writing my thesis in math, so people’s eyes usually glaze over the minute I start telling them what it’s about 😅 But of you want to give it a chance, I am studying hyperelliptic curves of genus 2 that have many points on a rank 1 subgroup of their Jacobian variety, trying to classify the types of curves that can occur. Don’t worry, even most of my math friends don’t understand what I’m doing 😂 It’s pretty much impossible to explain to people who don’t work in this field, so I guess there’s quite some truth to the saying that math is a lonely subject…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well yes, I didn’t understand a word of that, haha thanks for explaining anyway. It is humbling 🙂

I’m actually reading this novel, Folklorn (coming out in April) about a physicist who tries to negotiate reality vs. fiction, folktales narratives vs. science narratives— and I’ve been thinking a lot about my attitude towards math and sciences.

I always used to detest math and sciences in high school and in college. As I got older, I realized how that was because they’d taught it all wrong. Math and physics and sciences can be tools that can help us understand the universe and life itself. If someone , even a single teacher had told me that, my whole perspective on numbers would have shifted. Anyways, rambling over. All that to say, I’m sure your angle is quite interesting 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I completely agree! I think that the way math enables you to understand the world is a big reason why I’ve always loved it so much! That and how structured and logical it is 😊 Although I do also love the creativity and culture that comes with languages, which is why I went for a degree in both math and English 😅

And I might have to check out Folklorn! That concept sounds right up my alley!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Math and English sound like the perfect combo! Haha. They aren’t mutually exclusive at all. And yes, definitely, check out Folklorn once it’s out—you’d like it 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve discovered how to copy a link

Here are my posts about Damascus

https://wordpress.com/post/barbarakorzeniowska.com/2970

https://wordpress.com/post/barbarakorzeniowska.com/2086

https://wordpress.com/post/barbarakorzeniowska.com/2078

https://wordpress.com/post/barbarakorzeniowska.com/2063

https://wordpress.com/post/barbarakorzeniowska.com/2046

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Basia–I look forward to reading these!

LikeLiked by 1 person

hallo again; did you finish reading all those books. I seem not to have beenreceiving any posts from you for a while?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi again, and thanks for checking in! Yes, I’ve been MIA for a while, but I am back 🙂 I had to take a break from this list too, but I am currently reading one from Uzbekistan so it’s back on!

LikeLiked by 1 person

MIA?

LikeLike

Just meant, I haven’t been present here for a while 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person